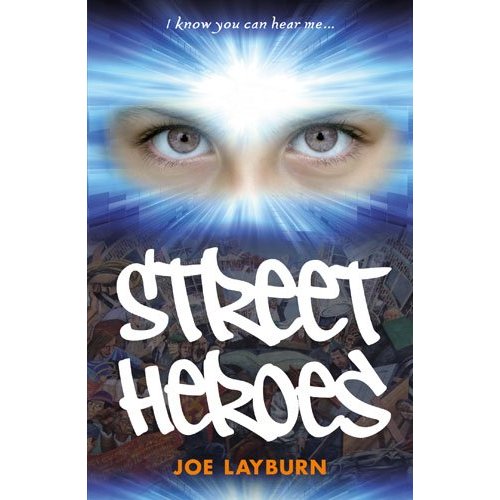

My next book for children, Street Heroes, will be published by Frances Lincoln in May 2010. It follows Ghostscape, which came out in 2008.

Here's my publishers' blurb for Street Heroes:

A brilliantly exciting adventure about a group of telepathic children taking a stand against evil.

Georgie's dad, George Smith is a highly controversial politician whose aim is to get rid of non-white people from London's East End. Everyone assumes Georgie shares his father's views, even his father. But while he loves his dad, he's really not sure what he thinks. And then he begins to hear a voice in his head, the voice of a Muslim girl called Fatima ...

My name is Fatima, I know you can hear me....

Meanwhile Fatima is also contacting other children in difficult situations, including Omar and Melissa. When an attempt is made to kill George Smith he responds by planning a repeat of the historical Battle of Cable Street when Fascists demonstrating against Jewish immigrants confronted local people. How can the mysterious Fatima and her gang stop Smith, and which side will Georgie be on?

By the acclaimed author of Ghostscape, this gripping story is a 'Heroes' for children dealing with issues of racism and immigration.

My name is Fatima, I know you can hear me....

Meanwhile Fatima is also contacting other children in difficult situations, including Omar and Melissa. When an attempt is made to kill George Smith he responds by planning a repeat of the historical Battle of Cable Street when Fascists demonstrating against Jewish immigrants confronted local people. How can the mysterious Fatima and her gang stop Smith, and which side will Georgie be on?

By the acclaimed author of Ghostscape, this gripping story is a 'Heroes' for children dealing with issues of racism and immigration.

This is how the story starts:

You know my dad. You’ve seen him on television, or on those massive posters, or even in the flesh. So you’ll understand why I could never be friends with someone who was black, or Asian, or different, in any way, from what I am - proper white British. That’s what I thought, until I started hearing voices.

It was at one of Dad’s rallies. There was a big crowd. There always was when he went to places like Barking, where lots of white people live on run-down estates.

Brian, one of Dad’s bodyguards, was getting twitchy, not so anyone else would have noticed, but I did. He was sweating, and he kept rubbing the back of his pockmarked neck. He had this thing stuck in his ear that meant he could hear what Tony and Mart were saying. The three of them, all built like heavyweight boxers, were not supposed to carry guns, but I imagined they did on days like this. They were always ready for trouble.

Some people loved my Dad. I know for a fact that Brian, Tony and Mart would have taken a bullet for him if they’d had to. But many people loathed him. And that’s because, as the do-gooders claimed, my Dad ‘spread racial hatred’.

When we first arrived at the Barking rally, a pale, skinny, blonde woman had leant in through the window of our car and shouted at Dad, “You’re a scumbag, Smith! My great-grandad died in the war trying to stop Nazis like you.” The press were there, their cameras clicking, so Dad just smiled back at her. “Nice to meet you too, darling.”

Whenever he was about to speak to a crowd, Dad looked like a preacher. His eyes shone and he glowed with a kind of religious excitement. He was wearing a dark suit, a white shirt with an electric blue tie, and the cufflinks my sister Albion had given him for his birthday. They had this Union Jack design and he kept fidgeting with them, which told me he was nervous too. Dad didn’t have a speech written down. Once he started, words just seemed to fly from his mouth like birds released from a cage. He stepped towards the microphone at the front of the platform and stretched out his arms for the crowd to be silent. Then he turned back to me and winked. I grinned at him and gave him the thumbs up.

“You all right?” he shouted, his voice hoarse and gravelly as always. It echoed round the town centre, bouncing off the shop windows and office buildings. “I said, are you all right?” This time the crowd called back that they were.

He paused for a beat or two, then shook his head, as if he couldn’t quite believe what he’d just heard.

“Well, when I look around this place, I’m surprised you say that. Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy if you’re happy. But to my mind, the people of Barking, the real people of Barking, deserve better than this. You deserve better than to have the refugees and the asylum-seekers and the illegals taking what’s rightfully yours. If that’s not a problem for you, then I made a mistake coming here. But if that’s something that worries you like it worries me, well, then I’m glad I came to speak to you today. In your hearts, people of Barking, don’t you think you deserve a lot more than you’re getting? Cos I reckon you’re being cheated out of your birthright. Am I right, or what?”

He cupped a hand to his right ear and this time they roared back at him like an incoming tide. I looked out at the white faces, raised arms waving little flags like you’d see on sandcastles at Southend or Clacton. And then the chanting started, like a rough sea beating against rocks: “Smiffy, Smiffy. . .” My dad, George Smith Senior glanced back again to where I was standing.

“Hear that, Georgie boy? These are our people.”

I started to smile but suddenly my head seemed to fill with a nuclear-size explosion, my body went rigid and the can of fizzy drink I’d been holding slipped through my fingers. It clattered down the side of the platform, but that noise was all but drowned out by what felt like wave upon wave of radio interference crashing around inside my skull. My mind was spinning wildly and when it finally stopped, someone else seemed to have grabbed control of it. A girl’s voice was speaking inside my head.

My name is Fatima. I know that you can hear me. Please don’t be afraid.

My vision had become distorted like a TV set on the blink, and I could feel myself swaying from side to side. Then Brian’s arm was around me, holding me up. Clearly he thought I was about to faint. I squinted hard and my dad’s anxious face swam slowly into view. I say anxious, but he looked annoyed too.

“What’s the matter with you, Georgie?” he hissed.

“I thought I heard this girl’s voice inside my head. She said her name was Fatima.”

“Fatima?” he growled. “You’re having a laugh.”

Here's a link so that you can pre-order Street Heroes:

http://www.franceslincoln.com/Book/7058/1/Street%20Heroes

Georgie

You know my dad. You’ve seen him on television, or on those massive posters, or even in the flesh. So you’ll understand why I could never be friends with someone who was black, or Asian, or different, in any way, from what I am - proper white British. That’s what I thought, until I started hearing voices.

It was at one of Dad’s rallies. There was a big crowd. There always was when he went to places like Barking, where lots of white people live on run-down estates.

Brian, one of Dad’s bodyguards, was getting twitchy, not so anyone else would have noticed, but I did. He was sweating, and he kept rubbing the back of his pockmarked neck. He had this thing stuck in his ear that meant he could hear what Tony and Mart were saying. The three of them, all built like heavyweight boxers, were not supposed to carry guns, but I imagined they did on days like this. They were always ready for trouble.

Some people loved my Dad. I know for a fact that Brian, Tony and Mart would have taken a bullet for him if they’d had to. But many people loathed him. And that’s because, as the do-gooders claimed, my Dad ‘spread racial hatred’.

When we first arrived at the Barking rally, a pale, skinny, blonde woman had leant in through the window of our car and shouted at Dad, “You’re a scumbag, Smith! My great-grandad died in the war trying to stop Nazis like you.” The press were there, their cameras clicking, so Dad just smiled back at her. “Nice to meet you too, darling.”

Whenever he was about to speak to a crowd, Dad looked like a preacher. His eyes shone and he glowed with a kind of religious excitement. He was wearing a dark suit, a white shirt with an electric blue tie, and the cufflinks my sister Albion had given him for his birthday. They had this Union Jack design and he kept fidgeting with them, which told me he was nervous too. Dad didn’t have a speech written down. Once he started, words just seemed to fly from his mouth like birds released from a cage. He stepped towards the microphone at the front of the platform and stretched out his arms for the crowd to be silent. Then he turned back to me and winked. I grinned at him and gave him the thumbs up.

“You all right?” he shouted, his voice hoarse and gravelly as always. It echoed round the town centre, bouncing off the shop windows and office buildings. “I said, are you all right?” This time the crowd called back that they were.

He paused for a beat or two, then shook his head, as if he couldn’t quite believe what he’d just heard.

“Well, when I look around this place, I’m surprised you say that. Don’t get me wrong, I’m happy if you’re happy. But to my mind, the people of Barking, the real people of Barking, deserve better than this. You deserve better than to have the refugees and the asylum-seekers and the illegals taking what’s rightfully yours. If that’s not a problem for you, then I made a mistake coming here. But if that’s something that worries you like it worries me, well, then I’m glad I came to speak to you today. In your hearts, people of Barking, don’t you think you deserve a lot more than you’re getting? Cos I reckon you’re being cheated out of your birthright. Am I right, or what?”

He cupped a hand to his right ear and this time they roared back at him like an incoming tide. I looked out at the white faces, raised arms waving little flags like you’d see on sandcastles at Southend or Clacton. And then the chanting started, like a rough sea beating against rocks: “Smiffy, Smiffy. . .” My dad, George Smith Senior glanced back again to where I was standing.

“Hear that, Georgie boy? These are our people.”

I started to smile but suddenly my head seemed to fill with a nuclear-size explosion, my body went rigid and the can of fizzy drink I’d been holding slipped through my fingers. It clattered down the side of the platform, but that noise was all but drowned out by what felt like wave upon wave of radio interference crashing around inside my skull. My mind was spinning wildly and when it finally stopped, someone else seemed to have grabbed control of it. A girl’s voice was speaking inside my head.

My name is Fatima. I know that you can hear me. Please don’t be afraid.

My vision had become distorted like a TV set on the blink, and I could feel myself swaying from side to side. Then Brian’s arm was around me, holding me up. Clearly he thought I was about to faint. I squinted hard and my dad’s anxious face swam slowly into view. I say anxious, but he looked annoyed too.

“What’s the matter with you, Georgie?” he hissed.

“I thought I heard this girl’s voice inside my head. She said her name was Fatima.”

“Fatima?” he growled. “You’re having a laugh.”

Here's a link so that you can pre-order Street Heroes:

http://www.franceslincoln.com/Book/7058/1/Street%20Heroes

Joe,

ReplyDeleteYour book cover is intense.It should serve you well. The prose is equally attractive. Good luck. Hope you sell a million.

Blessings,

The Differently-Abled Writer

www.jadaykennedy.com

http://jadaykennedy.blogspot.com

www.facebook.com/jadaykennedy.com

Coming this winter "Klutzy Kantor" picture book

http://klutzykantor.blogspot.com/